Part 1 - Reflective Practice and the Delivery of Disability Supports in Daily Life

Supporting another human in the care and support environment, requires you to reflect on your experiences, your interactions, responses, reactions, and behaviours. Understanding your style (of interaction) and reflecting on your practice, will enhance the experience for the person being supported or cared for, and will support you to grow into a considerate and adaptable worker.

Previously, I’ve talked about the ABC Model of Behaviour and touched on reflective practice as a means of delivering supports that remain relevant and wanted.

Here I want to talk more about reflective practice in the disability space, and its application in our daily work and life. I have broken the topic into two parts: part one is the application of reflective practice, and the delivery of disability supports in daily life; and two, the application of reflective practice in a support team setting.

Let’s start with its definition. What is reflective practice?

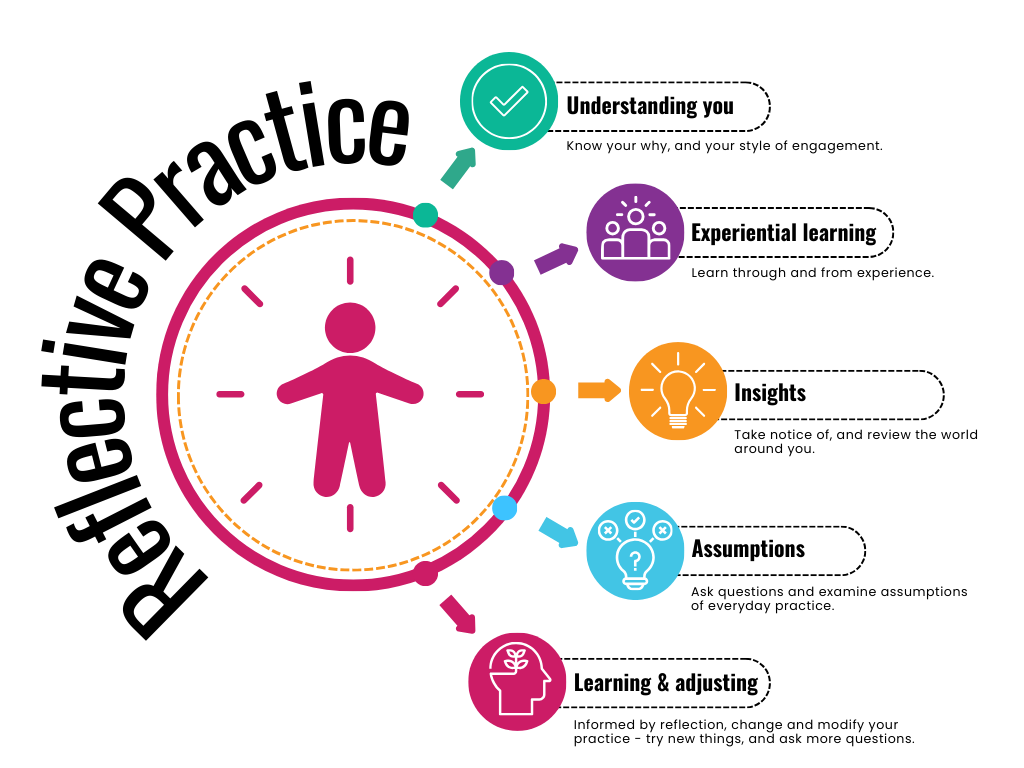

In her essay Reflecting on ‘reflective practice’, Linda Finlay defines it, “In general, reflective practice is understood as the process of learning through and from experience towards gaining new insights of self and/or practice. This often involves examining assumptions of everyday practice.” (2008).

Let’s run with this definition as it includes a number of important ideas and concepts we must consider when reviewing and reflecting on our experiences working with and supporting people with disability.

Words like, learning, and experience, insights, and self-practice, and the big one, assumptions.

There is no shortage of models to help us on our reflective practice way, and I have added some links for further reading at the bottom of this post for you to continue to develop and grow as professional reflective practitioners.

One of the first questions I like to ask people working in the disability sector is, why?

Why did you choose to work with and support people with disability? Why are you attracted to this type of work?

Naturally the answers vary – some have lived experience supporting someone with a disability; others feel they have the skills, abilities, temperament to make a positive difference in someone’s life. Many are drawn to this profession because they are caring people and have an empathy for others. Whatever it is for you, your why is your reason, and it’s the place where we begin our reflective practice story, and the place we should continuously revisit when we reflect on our practice of providing supports.

Without thinking, most of us employ reflective practice in our daily lives. We ask questions of ourselves and others to avoid making assumptions, to get to know one another, and to improve our relationships.

For example, you dine out at a local restaurant for the first time with a friend. Did your enjoy your meal? Did you think the food was too expensive? Do you think it took too long to get served?

While simple, these questions lead to the act of reflection, and your answers will determine whether you frequent this restaurant again, or give it a miss in the future.

Let’s apply the same reasoning to supporting people in their daily lives.

Do you ask if someone has enjoyed their day, or liked the activity they just did with you, or if they liked the people they met. Unless they volunteer the information or you learn their thoughts or feelings another way, you will be caught in an endless cycle of assumptions.

The act of curiously asking questions is one of the most meaningful ways you can avoid making assumptions and support someone to do the things they want to do, or do the things they have to do, in a way that’s ok with them.

This is the fundamental principle of behaviour supports – and one of the first considerations of reflective practice.

Let’s revisit the why question again in terms of providing supports. If your why is to make someone’s life better, and your job is to get the person out of bed and showered but they say they‘re tired and want to sleep in… how do you react?

Do you say, sorry but you have to get up? Or do you tell them that you‘ll come back later so they can have a sleep in. Just like that, now becomes the perfect time to do something else on your ‘to do’ list.

In this scenario, the person’s need for a sleep-in has been met, and you have managed to work your way through some of the things you need to do. It is a happy win: win for everyone.

This may sound basic to some people but it’s surprising how many vigilant workers I meet who think that it’s more important to do what they need to do, rather than what the other person wants to do. This is where insight comes into play.

In its essence, “insight is the power or act of seeing into a situation”. (Merriam-Webster, 1828) So it follows that the ‘power of insight’ in a support role, means to continuously review the world around you, take notice, reflect, and learn, and if necessary, modify what is happening, plan and try new things, and ask more questions.

Having insight into a person’s situation or circumstances, means that your understanding about them and their environment is enhanced, and the way you provide supports is more responsive to the person’s needs and desires.

This act of planning, doing, reflecting, and re-doing is the framework for all reflective practice.

Don’t forget to ask, what worked well?

Reflective practice is not just about reflecting on the things that have not worked well – it’s also about reflecting on the things that seem to have worked well. An outcome of reflective practice is not always about changing or adapting, it may also be about confirming the positive experiences and activities and identifying why they went well.

This leads us to assumptions…

People who cannot tell us what they’re thinking or feeling with words will find another way to tell us – it’s our job to remain attentive, learn the cues, engage in a positive way, and reflect on our practice.

For a lot of people with disability, their support team workers are the most influential people in their lives, so reflecting on your role and your practice in a person’s environment is paramount and will have a significant impact on a person’s quality of life, sometimes in ways we can’t know or see.

This is a good time to remind ourselves that while this is our work, this is their life.

Our role is to work with people with disability to support their needs, not to support our needs. If a support situation is going badly, stop and ask yourself, “who am I here to serve?” and make sure what you are doing is more about meeting the other person’s needs, rather than your own.

Imagine that you have the disability and you’ve never been asked what you think or how you feel about doing ‘something’. Imagine that the people supporting you have made a whole series of assumptions about what they think you want and like and most of the time they’re wrong. Imagine how frustrating that would be.

People are people regardless of their disability or condition, and when we accept this, we can reflect on how they express their needs and wants with us and how they would like to be supported and treated. If we take the time to get to know a person and not make assumptions about them, and what they want and need based on their disability or condition, we will be truly providing responsive person-focused supports.

To close, I think it only fair to share my why:

I study and work in the field of psychology to learn about people and their behaviours under differing circumstances, so that I might be better equipped to identify when someone is saying something to me that I need to pay attention to.

I see every day as an opportunity to grow as I reflect on how my day has gone, what my interactions with others were like, and what I might have done differently if given the time over again.

In part two, I will talk about collective reflective practice, and offer you a framework to guide your reflection in a group setting.

Until then, ask questions, listen, watch, and learn.

Brett

Brett Fitzsimmons

Psychologist & Positive Behaviour Support Practitioner

Brett Fitzsimmons is our on-site psychologist with more than 20 years’ experience working with children and adults with disability, and psychosocial disability. He is a NDIS Registered Behaviour Support Practitioner. Read more about Brett.

Let’s talk about how we can be part of your story.

Supports we offer

Why choose CSBS

CSBS Connect – Access support information in real time.

CSBS is a NDIS Registered Provider – what that means for you.

About CSBS

Registered NDIS Provider No: 4050093808 - Complex Supports Bespoke Solutions

Contact Us

Level 1, 673-679 David Low Way, Mudjimba, QLD 4654

1300 18 11 88